Teaching Now: Analyzing Primary Sources for Scientific Thinking & Organization

This is a guest post from Tom Bober (a.k.a. @CaptainLibrary), an elementary librarian at RM Captain Elementary in Clayton, Missouri and frequent contributor to the TPS Teachers Network.

Earlier this school year I wrote about an activity in which third grade students analyzed primary sources from the Library of Congress, specifically the notes, diagrams, and writings of scientists to explore how scientists organize information. The hope was that students would connect these organizational examples to their own attempts to organize their scientific thinking through science notebooking that they would work on throughout the school year.

With the school year is coming to a close, I thought it was the perfect time to check in with students about how their scientific notebooking had progressed. This was a new activity for them and there were lots of opportunities for individual students to decide how to organize scientific data gathered for various projects.

As I planned to revisit with students, I had two wonderings. First, how had students’ organization evolved through their first year of scientific notebooking? Second, how adept would students be at analyzing their own scientific notes to observe and reflect on organizational structures?

I decided that the primary sources we would look at would shift from analyzing the work of known scientists to analyzing their own work which was, in fact, newly created primary sources related to scientific thinking and organization.

First I asked students to do a verbal, group analysis of a scientist’s notes that they had not seen before, a portion of a drawing by Georg Ehret showing Carl Linnaeus’ division of the vegetable world. I asked students to focus on the scientific thinking as we followed the structure of the Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis Tool by making observations, reflections, and asking questions.

- What evidence of scientific thinking did they see?

- How did they think the artist was trying to organize ideas?

- What questions did they have about the organization methods?

Some of their observations are listed below and many clearly connected to CCSS text connection skills they had practiced this year.

- “The drawings are of different things.”

- “Captions”

- “Labels in alphabetical order”

Student reflections built on observations were unique to how they perceived these notes being organized. What I felt was worth noting was that even though students weren’t sure why this drawing was made, they used the observed organization methods to try to understand the information, as highlighted in the student comments below.

- “He’s using dotted lines to connect the drawings of plants and roots.”

- “He could just be showing how plants grow.”

- “The dotted lines might show combining plants together to make a new plant.”

We then moved on to analyze student scientific notes. “The next primary sources we are going to look at are ones that you created. You have been scientists at different times this year and have taken notes just like the scientists notes that we analyzed. How did you organize your work? How did your organizational methods help to explain the work that you did?”

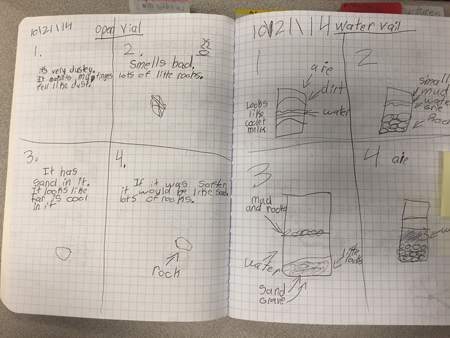

I chose a few student volunteers to share their work, letting them know that we were going to analyze their notes too. In one example, a student shared her notes from observations she made in an October science class, about two months after our original activity (see image at the top of this post).

Many similar observations were made when the children were asked to look for evidence of how this student scientist had organized her thinking.

- “pictures”

- “labels”

- “numbered boxes”

- “dates”

- “notes”

When children were asked to reflect on their observations to “make sense” of the student-scientist’s notebooking, different opinions started to emerge on how she organized her work as well as differences in how to describe her organization.

- “I’m glad she numbered the boxes. I think these might compare the two.”

- “Labels and arrows help me understand the pictures.”

- “more writing for one and the other has more drawling”

- “reminds me of Venn diagram”

- “I like the pictures better than the writing.”

- “I really like that she put everything in boxes to make it understandable.”

- “t-chart”

As students shared their reflections, the student scientist listened intently. After our analysis, her initial thoughts were around wanting to change her organization. “I felt like I could have gone back in time and fixed things,” she noted, referring to using more pictures in one part of her notes.

This student then talked more about how she organized her work and how others saw that organization. Reacting to a large part of the class thinking that her notes could be seen as a type of Venn diagram, she seemed surprised. “I, no where, no how, even thought of that!” Maybe even more surprising to her was how she saw her own scientific notes organized. “I thought it looked like a t-chart [when we analyzed the notes], but I didn’t think that when I made it.”

The last statement struck me. The student scientist didn’t make a conscience effort to organize her notes in a specific way, but later saw organizational structures that she had used intuitively. We often tell students to use a teacher-prescribed structure to take notes such as bulleted lists, Venn diagrams, t-charts, webs; the list is long. But we don’t want it to end there. We want students to organize their ideas in ways that work best for their understanding of the content and then, when appropriate, to convey that content in a way that will make sense to the intended audience.

Did analyzing the notes of scientists earlier in the year help her think beyond the taught organizational methods? I’m not sure. What I am sure of is that this early analysis showed all of the students that there are a variety of ways that scientists organize their thinking and that it is useful to reflect on our own organizational thinking as well as to consider how that organization is conveyed to other audiences. In this way, students were able to make connections to curriculum objectives while also being encouraged to go beyond and extend their learning.

¹ “Item of the Month No. 8 (April 2011).” NaturePlus blog, Apr 1, 2011. Natural History Museum, London. Accessed May 13, 2015.