Learning from the Source: Indian Territory Resettlement

![Indian territory [1887]: compiled from the official records of the records of the General Land Office and other sources under supervision of Geo. U. Mayo. Indian territory [1887]: compiled from the official records of the records of the General Land Office and other sources under supervision of Geo. U. Mayo.](https://primarysourcenexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/INTerritory.jpg)

In his article, “Thinking Like an Historian“, from the TPS Quarterly archive (now the TPS Journal), Sam Wineburg points out how many students’ view of history—memorization—diverges from that of historians—investigation—and offers advice for using primary sources to engage students in the “historical approach”. Doing so will help students make more authentic and lasting connections to important historical themes and events as well as give them practice in key Common Core State Standards in English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies (CCSS).

The activity outlined below was originally created by TPS-Barat for the Chicago Public Schools Social Science 2.0 “Circles of Citizenship” Professional Development Academy and is designed for secondary students; select sources may also be useful for middle school students.

Guidelines

Arrange the various source sets in inquiry centers and have students analyze the sources in small groups. Because the maps are best viewed online using the Library’s zoom feature, you may choose to analyze this source set as a class.

Students will use the primary source analysis tool and the guiding questions to analyze the six primary source sets; you may also use the CCSS alignments (see end of post) to generate additional avenues of investigation. After students have finished their primary source analyses, discuss their findings. What different viewpoints did they discover?

Extension: Have students review more primary sources as well as secondary source information. After, discuss how that information adds to their overall understanding of the big idea and focus question.

Big Idea

Movements of populations have economic, social and political causes and effects.

Focus Question

Why were Native Americans resettled to Indian Territory and how were they affected by changes in government policies and non-native settlement during the 19th and early 20th centuries?

Map Source Set

MAP 1

Map showing the lands assigned to emigrant Indians west of Arkansas and Missouri

United States. Topographical Bureau

Published 1836.

Notes

– From: [Documents concerning Col. Henry Dodge’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains], House Document 181, 24th Cong., 1st session, 1835-36, serial 289.

– LC Many nations, 200

– Exhibition: Indians of North America, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., August, 1977.

http://www.loc.gov/item/99446197

MAP 2

Indian Territory, with Part of the Adjoining State of Kansas

United States. Army. Corps of Topographical Engineers

Published 1866. Washington, D.C. : Engineer Bureau, War Dept.

Notes: “Prepared from the Map of Danl. C. Major, U.S. Astt. showing the boundaries of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, the Creek, Seminole, and Leased Indian Country established by authority of the Commrs. of Indian Affairs in 1858-59. and from Lieut. Col. J.E. Johnston’s Map of teh Southern Boundary of Kansas in 1857. The Map of the Creek Country by Lieut. L. C. Woodruff, Topl. Engrs., in 1850-51.”

http://www.loc.gov/item/2011590003

MAP 3

Indian territory: compiled under the direction of the Hon. John H. Oberly, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, by C.A. Maxwell.

Published 1889.

Notes: Shows the lands occupied by various tribes and includes details about land transfers and cessions.

http://www.loc.gov/item/98687105

MAP 4

Map of the Indian And Oklahoma Territories, 1894; compiled from the official records of the General Land Office and other sources

Rand McNally and Company, Chicago.

Notes

– Scale 1:760,320.

– LC Railroad maps, 288

– Description derived from published bibliography.

– Shows relief by hachures, drainage, Indian areas, districts, treaty dates, roads and trails, and the named railroads.

http://www.loc.gov/item/98688546

MAP 5

Premier Series Map of Oklahoma and Indian Territory

Published 1905, Geographical Publishing Co.

Notes: “Indian nations and Indian, forest, grazing, saline, and wood reservations shown by red boundaries.”

http://www.loc.gov/item/2001620495

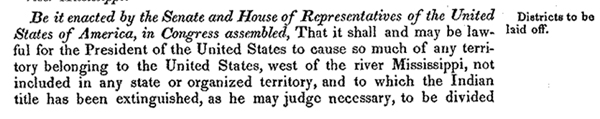

Source Set 1

SOURCE 1A

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=004/llsl004.db&recNum=458

SOURCE 1B

Approved on February 8, 1887, “An Act to Provide for the Allotment of Lands in Severalty to Indians on the Various Reservations,” known as the Dawes Act, emphasized severalty, the treatment of Native Americans as individuals rather than as members of tribes.

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/dawes.asp

Guiding Questions

Observe

- What type of text is this (letter, newspaper article, report, advertisement, legal document, etc.)?

- Are there any headers, headlines or other formatting options that call out specific parts of the text?

- When was this text created? Is place relevant to this text? How?

- What does the text describe or explain?

- What specific details are mentioned? What rights were given to the President? What rights were given to the Indians?

Reflect

- Why do you think the creators chose to include these specific details of description or explanation? What information might have been left out of the text?

- Does this text show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What do you feel when reading this text?

- What did you learn from examining this text? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this text?

Compare & Contrast

- What similarities or differences do you find in the language of the two texts? What changes do you notice in the attitude of the U.S. government towards the Native Americans?

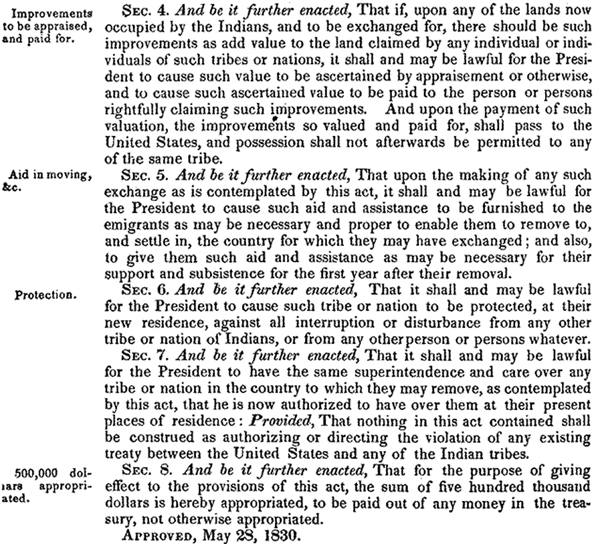

SOURCE 1A (excerpt)

“An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians . . .” May 28, 1830

SOURCE 1B (excerpt)

“An Act to Provide for the Allotment of Lands in Severalty to Indians on the Various Reservations” (Dawes Act) February 8, 1887

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That in all cases where any tribe or band of Indians has been, or shall hereafter be, located upon any reservation created for their use, either by treaty stipulation or by virtue of an act of Congress or executive order setting apart the same for their use, the President of the United States be, and he hereby is, authorized, whenever in his opinion any reservation or any part thereof of such Indians is advantageous for agricultural and grazing purposes, to cause said reservation, or any part thereof, to be surveyed, or resurveyed if necessary, and to allot the lands in said reservation in severalty to any Indian located thereon in quantities as follows: To each head of a family, one-quarter of a section; To each single person over eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; To each orphan child under eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; and To each other single person under eighteen years now living, or who may be born prior to the date of the order of the President directing an allotment of the lands embraced in any reservation, one-sixteenth of a section: Provided, That in case there is not sufficient land in any of said reservations to allot lands to each individual of the classes above named in quantities as above provided, the lands embraced in such reservation or reservations shall be allotted to each individual of each of said classes pro rata in accordance with the provisions of this act: And provided further, That where the treaty or act of Congress setting apart such reservation provides the allotment of lands in severalty in quantities in excess of those herein provided, the President, in making allotments upon such reservation, shall allot the lands to each individual Indian belonging thereon in quantity as specified in such treaty or act: And provided further, That when the lands allotted are only valuable for grazing purposes, an additional allotment of such grazing lands, in quantities as above provided, shall be made to each individual.”

SEC. 3. That the allotments provided for in this act shall be made by special agents appointed by the President for such purpose, and the agents in charge of the respective reservations on which the allotments are directed to be made, under such rules and regulations as the Secretary of the Interior may from time to time prescribe, and shall be certified by such agents to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in duplicate, one copy to be retained in the Indian Office and the other to be transmitted to the Secretary of the Interior for his action, and to be deposited in the General Land Office.

SEC. 6. That upon the completion If said allotments and the patenting of the lands to said allottees, each and every number of the respective bands or tribes of Indians to whom allotments have been made shall have the benefit of and be subject to the laws, both civil and criminal, of the State or Territory in which they may reside; and no Territory shall pass or enforce any law denying any such Indian within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law. And every Indian born within the territorial limits of the United States to whom allotments shall have been made under the provisions of this act, or under any law or treaty, and every Indian born within the territorial limits of the United States who has voluntarily taken up, within said limits, his residence separate and apart from any tribe of Indians therein, and has adopted the habits of civilized life, is hereby declared to be a citizen of the United States, and is entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities of such citizens, whether said Indian has been or not, by birth or otherwise, a member of any tribe of Indians within the territorial limits of the United States without in any manner affecting the right of any such Indian to tribal or other property.

SEC. 8. That the provisions of this act shall not extend to the territory occupied by the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles, and Osage, Miamies and Peorias, and Sacs and Foxes, in the Indian Territory, nor to any of the reservations of the Seneca Nation of New York Indians in the State of New York, nor to that strip of territory in the State of Nebraska adjoining the Sioux Nation on the south added by executive order.

SEC. 9. That for the purpose of making the surveys and resurveys mentioned in section two of this act, there be, and hereby is, appropriated, out of any moneys in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, the sum of one hundred thousand dollars, to be repaid proportionately out of the proceeds of the sales of such land as may be acquired from the Indians under the provisions of this act.

SEC. 10. That nothing in this act contained shall be so construed to affect the right and power of Congress to grant the right of way through any lands granted to an Indian, or a tribe of Indians, for railroads or other highways, or telegraph lines, for the public use, or condemn such lands to public uses, upon making just compensation.

Source Set 2

SOURCE 2A

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llrd&fileName=010/llrd010.db&recNum=438

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llrd&fileName=010/llrd010.db&recNum=439

SOURCE 2B

The condition of affairs in Indian Territory and California. A report by Prof. C.C. Painter, agent of the Indian rights association.

Painter, C. C. (Charles Cornelius)

Philadelphia, Indian rights association, 1888.

{Begin page no. 11}

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gdc/calbk.052

Guiding Questions

Observe

- What type of text is this (letter, newspaper article, report, advertisement, legal document, etc.)?

- When was this text created? Is place relevant to this text? How?

- What does the text describe or explain?

Reflect

- Why do you think the author chose to include these specific details of description or explanation? What information might have been left out of the text?

- Does the text show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What do you think the author might have wanted the audience to think or feel?

- What do you feel when reading this text?

- What did you learn from examining this text? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this text?

Compare & Contrast

How does President Jackson’s view of Native American resettlement compare to what C.C. Painter reports?

SOURCE 2A (excerpt 1)

President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress On Indian Removal. December 6, 1830

SOURCE 2A (excerpt 2)

SOURCE 2B (excerpt)

“The condition of affairs in Indian Territory and California” 1888

OKLAHOMA. Owing to the impassable condition of the streams, my plan for visiting the Sac and Fox people, and the Shawnees and Pottawatomies, had to be abandoned. From Pawnee I went down through the Oklahoma country to Oklahoma station, (on the A. T. and Sante Fe Branch Road, which now connects through to Galveston, Texas) where stages connect for Darlington and Ft. Reno. This gave opportunity to see the character of this famous, much-coveted country. It is better timbered and watered than any other portion of the Indian Territory I have seen, and grass is abundant; but I do not believe the soil is so good as either east or west of it. It would not better the Wichitas, and the other Indians whom it is proposed to remove into it, so far as the quality of the land is concerned. It is not, as many seem to suppose, the original site of the Garden of Eden, but is far too good a country to be suffered to lie unused when so many of our citizens are seeking homes.

I was asked, both by the President and Mr. Lamar, to give an opinion as to the advisability of removing the Indians west of Oklahoma into this district, so that the reservations now occupied by them might be opened to settlement. After an extended tour and inspection of their reservations, and inquiries into their condition and prospects, I reported that in my estimation it would be unjust, cruel and disastrous to do so.

The theory on which this is proposed is that no treaty stands in the way of their removal, or of the opening of their reservations, since they are on executive order reservations, while there are treaty and other difficulties in the way of throwing open Oklahoma to white settlement.

These reasons are valid in appearance only, but not in reality, while there are very real and urgent reasons why it should not be done. A treaty was made with the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, for instance, giving them a reservation north of the one now occupied, but we had no right to give them this land, it being in part embraced in the Cherokee outlet, and the Indians did not understand that it was the land for which they were treating, but supposed they were getting the land which is now occupied by them. They refused to move upon it, and we had no right to remove them to it. After correspondence, the President set apart, by “Executive order,” their present reservation, in lieu of that given them by the treaty. Of course he had no power to annul, by Executive order, their treaty rights, among which was the right of any individual Indian, head of a family, to have allotted to him 320 acres of land to be secured by a patent. If the President could rightfully give them this land in lieu of the other, their possession of it carried with it all the rights they had on the other tract.

The Wichitas are said to be on a reservation by unratified treaty, and since the treaty has never been ratified by the Senate there could be no legal obstacle to their being removed. The fact is, these Indians claim always to have been the owners of this land, not only of what they occupy, but of a large body occupied in part by the Kiowas and Comanches, Delawares and Caddoes, and also that which was procured from the Quapaws for the Chickasaws, we treating with those Kansas Indians for land owned by them. Their title to it has never been extinguished. So there are virtual legal and treaty obligations in the way of this removal, fully as sacred as those which prevent us from opening Oklahoma, and certainly the moral obligations are even greater. These people, especially the Wichitas, have taken deep root in these lands, have built them homes, and opened up farms. This is being done with most encouraging rapidity by the Cheyennes, Arapahoes and Comanches. It would be a cruel outrage to force them to remove; it would be a disastrous step backward to induce them to go. The lands to which they would remove are not so good as those now occupied; they are bitterly opposed to the plan and it ought not to be attempted. Oklahoma ought to be opened up. It is not needed by the Indians, it cannot be kept empty and ought not to be so kept; but if treaty and moral obligations must be violated, it is better to do so with reference to vacant lands than with reference to established homes. Steps ought to be taken at once to gain the consent of the Seminoles and Creeks to throw this land open to settlement, and it could doubtless be done if a fair price above the thirty cents per acre which we paid for it, for the settlement of Indians upon it, was offered for it.

We know from good authority that an empty house, though swept and furnished, cannot be guarded against demoniacal possession. The only way to keep it clean is to occupy it. But we ought to have learned something from past experience in regard to the removal of Indians from their homes to satisfy the convenience or the greed of the white man. Much and bitter complaint has been made that the President has failed to appoint a Commission, which he was authorized to do, to treat with the Indians of the territory for a surrender of their treaty rights in regard to land. The appointment of such a Commission, simply to treat with them for their consent, is seemingly a very innocent and proper thing to do, but it is very much like the act of March 1st, 1883, empowering the President to consolidate agencies and tribes, at his discretion, “with the consent of the tribes to be affected thereby, expressed in the usual way,” which J. P. Dunn, Jr., interprets to mean “The President is authorized and empowered to drive the Indians from their native homes, and place them on unhealthy and uncongenial reservations, whenever sufficient political influence has been brought to bear upon the Commissioner of Indian Affairs or the Secretary of the Interior, by men who desire the lands of any tribe, to induce a recommendation for their removal. Provided, that before any tribe shall be removed the members thereof shall be bullied, cajoled or defrauded into consenting to the removal.” Mr. Dunn reminds us that the Modoc war was caused by attempting to force these Indians to stay on a reservation with the hostile Klamaths, who would give them no peace, nor allow them to raise food. The Sioux war of 1876 resulted from an enforcement of an order for that nation to abandon the Powder River country, which we had guaranteed them as a hunting ground, and to limit them to their reservation, where there was no game.

The Nez Perce war of 1877 was caused by an attempt to force Joseph’s band of Lower Nez Perces to abandon their own home, their title to which had never been extinguished, and go upon the Lapwai Reserve.

All our troubles with the Chiracahua Apaches since 1876 have come from our attempts to remove them from their native mountains to an unhealthy and intolerable place for mountain Indians, to live with a band unfriendly to them. The wars with Victorio’s Apaches resulted from the discontinuance of their reservation, and an order for their removal to San Carlos. The war with the northern Cheyennes came from an attempt to make them stay in the Indian Territory, which proved unhealthy for them. The shame and disgrace of the Ponca removal is yet fresh in mind, and a war, which would have marked the path hewn by them from the Indian Territory back to their old home in Nebraska, would have been a legitimate outcome of this outrage had Standing Bear’s band been stronger.

The Hualapais, removed to the Colorado River, escaped extermination, so unhealthy was the new home, only by fleeing from it in a body. The list might be indefinitely extended, but those who make our laws touching Indian affairs, and those entrusted with their administration, seem incapable of learning anything from the history of the past.

The present Commissioner of Indian Affairs returns, in his last report, to his recommendations in regard to the removal of the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, Wichitas and associated tribes, so that the clamor about Oklahoma may be hushed, and politicians, urged forward by their constituents who want these lands, are unwearied in their efforts to have this outrage committed. The friends of the Indian ought to take tenable ground in their opposition to this, lest in mistaken efforts to maintain, pro forma, the exact proportions of the treaty, or other rights of these people, they shall lose all. We may as well settle it first as last, and better now than later, that such an immense territory as now lies vacant and worse than useless under the shadow of old treaties, can never, as a matter of fact, be held for such time as the Indian, left to himself, may be able to utilize it and cause it to contribute what it is capable of doing to meet the world’s cry for food. But a successful appeal may be hopefully made to the American people as against essential and absolute injustice and cruel wrong, and this appeal should be promptly and distinctly made.

It is already apparent that the time of the land-grabber is short, and that what he does to rob the Indian of his land must be done quickly, before the severalty law gives it to him by an inalienable title. Efforts in this direction will be earnest and unremitting; the vigilance and efforts of the Indians’ friends must not be less so.

Source Set 3

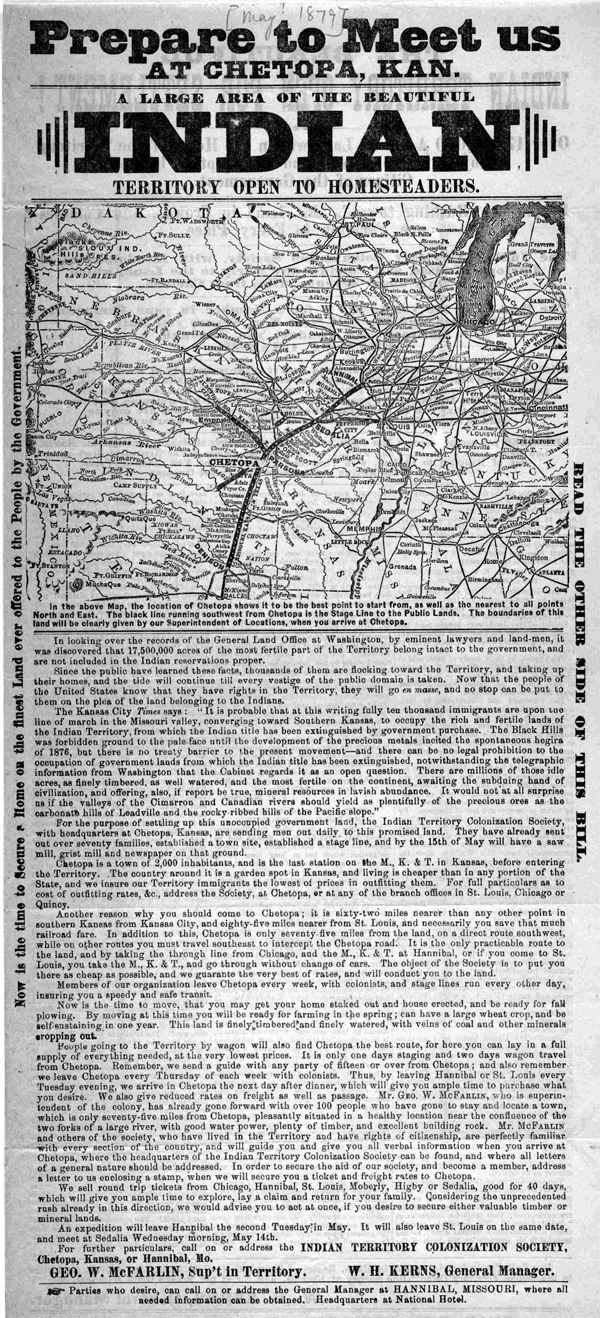

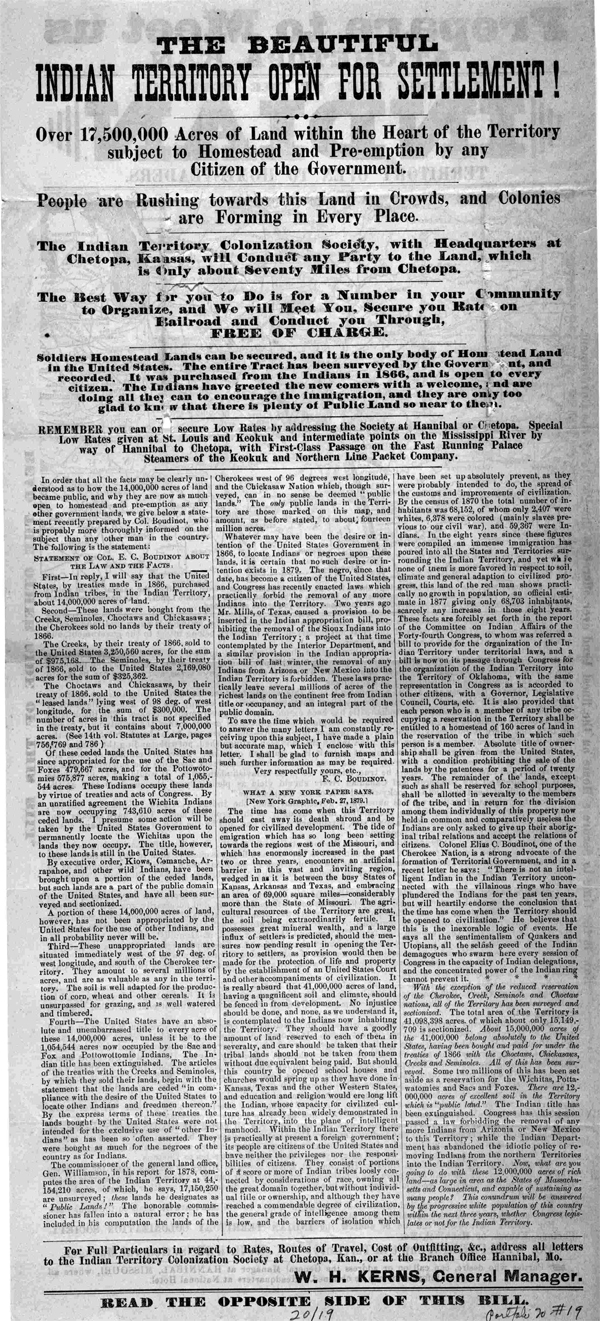

SOURCE 3A

Prepare to meet us at Chetopa, Kan. a large area of the beautiful Indian territory open to homesteaders … for further particulars, call on or address the Indian Territory Colonization Society

Indian Territory Colonization Society

Published Chetopa, 1879

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/h?ammem/rbpebib:@field(NUMBER+@band(rbpe+02001900))

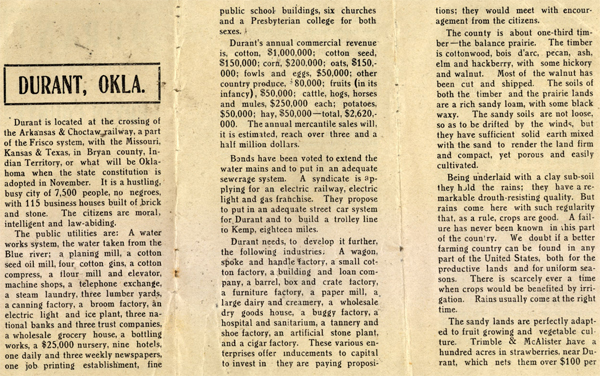

SOURCE 3B

Durant, Indian Territory and Bryan County

Published1906, Citizens Loan & Realty Co.

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.award/ncdeaa.A0579

Guiding Questions

Observe

- What type of text is this (letter, newspaper article, report, advertisement, legal document, etc.)?

- Are there any headers, headlines or other formatting options that call out specific parts of the text?

- What does the text describe or explain?

– What specific benefits does the advertisement list for meeting at Chetopa, Kansas? What does the map show?

– What specific benefits does the advertisement list for Durant, Oklahoma/Indian Territory?

Reflect

- Why do you think this text was made? What might have been the creator’s purpose? What evidence supports your theory?

- Why do you think the creator chose to include these specific details of description or explanation? What information might have been left out of the text?

- Who is the audience for the text? What do you think the creator might have wanted the audience to think or feel? Does the arrangement or presentation of words, illustrations, or both affect how the audience might think or feel? How?

- What do you feel when reading this text?

- Does this text show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What did you learn from examining this text? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this text?

Compare & Contrast

- How are these sources similar and how are they different? Which is more appealing to you? Why? Which seems more realistic? Why?

SOURCE 3A (1879)

SOURCE 3B (1906)

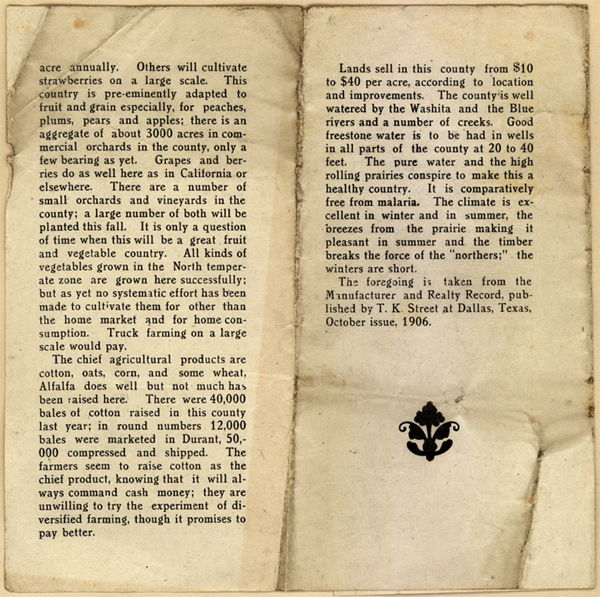

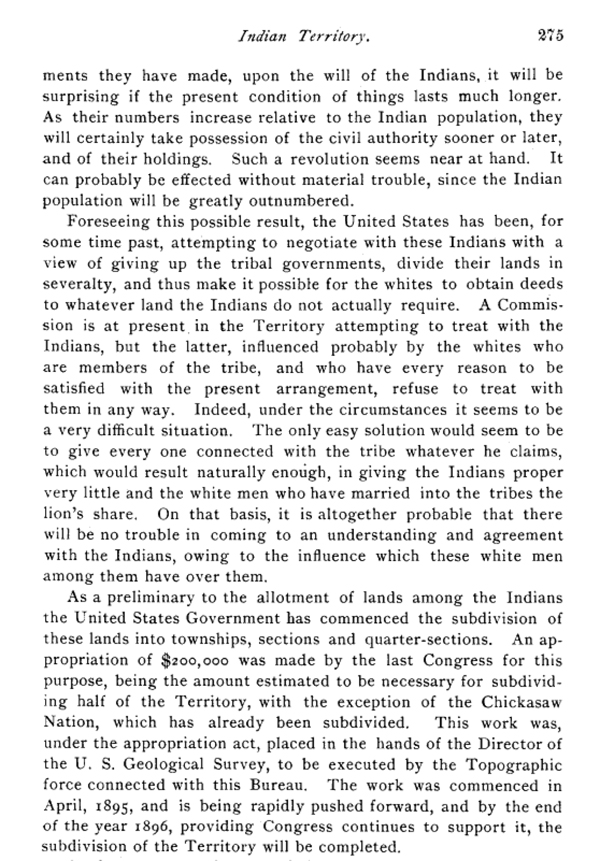

Source Set 4

SOURCE 4A

Indian Territory

Gannett, Henry

46 pages, published 1881, New York, C. Scribner’s sons

http://archive.org/details/indianterritory00gann

SOURCE 4B

“Indian Territory”

Gannett, Henry

Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1895), pp. 272-276

http://www.jstor.org/stable/197313

Guiding Questions

Observe

- What type of text is this (letter, newspaper article, report, advertisement, legal document, etc.)?

- Are there any headers, headlines or other formatting options that call out specific parts of the text?

- What does the text describe or explain?

- How does the text portray the Native Americans and the U.S. government?

Reflect

- Why do you think this text was made? What might have been the creator’s purpose? What evidence supports your theory?

- Why do you think the author chose to include these specific details of description or explanation? What information might have been left out of the text?

- What do you think the author might have wanted the audience to think or feel? Does the arrangement or presentation of words, illustrations, or both affect how the audience might think or feel? How?

- What do you feel when reading this text?

- Does this text show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What did you learn from examining this text? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this text?

Compare & Contrast

- What was the tone of each text? How did the author portray the Native Americans and the U.S. government in the text from 1881 versus the text from 1895? What do you think accounts for the similarities or differences in the portrayals?

SOURCE 4B (excerpt)

“Indian Territory” 1895

Source Set 5

SOURCE 5A

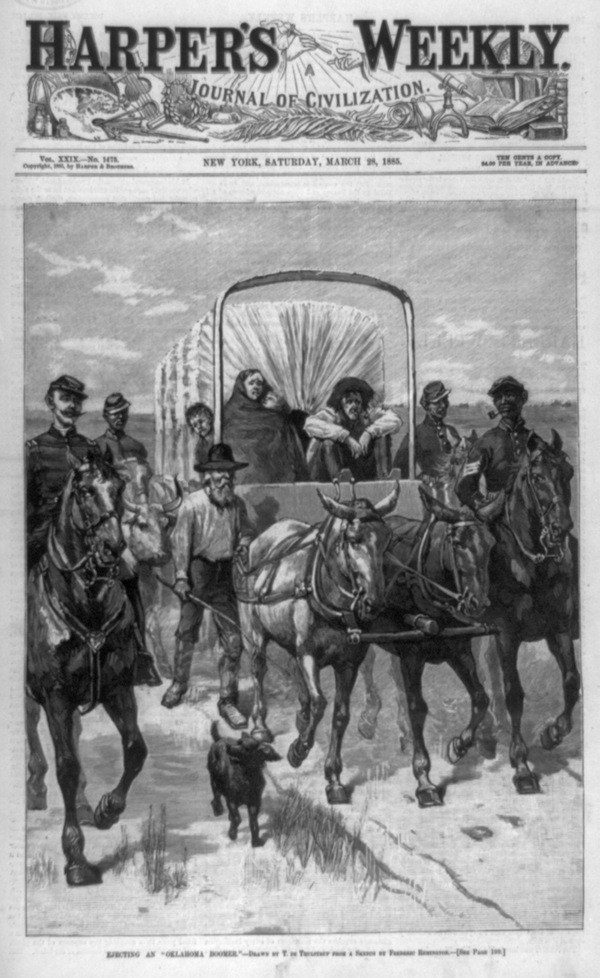

Ejecting an “Oklahoma boomer” / drawn by T. de Thulstrup from a sketch by Frederic Remington.

1885 March 28

wood engraving.

Summary: Squatter family in wagon being escorted by soldiers from Indian territory

Notes: Illus. in: Harper’s weekly, 1885 March 28, cover

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/89714477/

SOURCE 5B

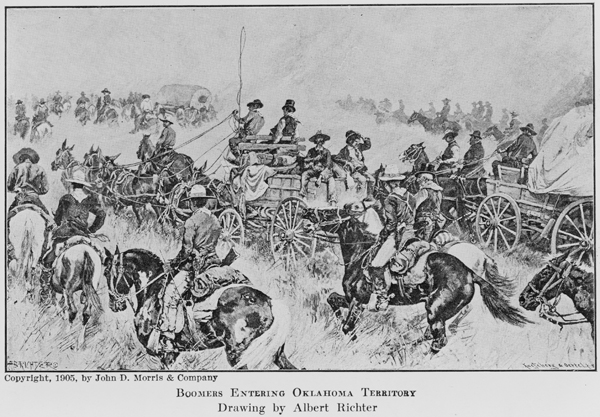

Boomers entering Oklahoma Territory

c1905

photomechanical print : halftone

Notes: F39291 U.S. Copyright Office

Reproduction of drawing by Albert Richter

Copyright by John D. Morris & Company

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/94506348/

Image Guiding Questions

Observe

- What type of image is this (photo, painting, illustration, poster, etc.)?

- What do you notice first? Describe what else you see.

- What is the physical setting? Is place important?

- What people and objects are shown? How are they arranged? How do they relate to each other?

- What words, if any, do you see?

Reflect

- Why do you think this image was made? What might have been the creator’s purpose? What evidence supports your theory?

- Why do you think the creator chose to include these particular details? What might have been left out of the frame?

- What do you think the creator might have wanted the audience to think or feel?

- What do you feel when looking at this image?

- Does this image show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What did you learn from examining this image? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this image?

Compare & Contrast

- What do you think accounts for the similarities or differences in the portrayals of the Boomers in the two images?

SOURCE 5C

Interview about Oklahoma

1940/08/05

Interviewee: Robertson, Mrs. Flora

Genre: Conversation

Notes: Mrs. Flora Robertson talking about Oklahoma.

Location: Shafter FSA [migrant labor] Camp

http://www.loc.gov/item/toddbib000090/

Guiding Questions

Observe

- Where does the recording take place?

- Is the recording taking place around the time of the events described or later? If later, how much later?

- Is the content easy or difficult to understand because of vocabulary or accent?

- What does the recording relate, describe, or explain?

- What specific details about Boomers and settlement does this oral history provide?

Reflect

- Why do you think this oral history was captured? What might have been the purpose of preserving this oral history? What evidence supports your theory?

- Does this oral history show clear bias? If so, towards what or whom? What evidence supports your conclusion?

- What do you think the interviewer wanted the audience to think or feel about the subject or topic of the oral history?

- What do you feel when listening to this oral history?

- What did you learn from this oral history? Does any new information you learned contradict or support your prior knowledge about the topic of this image?

Compare & Contrast

- How does the representation of Boomers that this oral history presents compare with the representations presented in the images? Are they more alike or unlike? In what way(s)?

- Consider the primary sources you have analyzed (and, possibly, credible secondary source information), then think how you would respond to the following: Who were the Boomers? What racial and ethnic group(s) did they include? How did they view their settlement in Indian Territory? What details support your conclusions?

SOURCE 5A

“Ejecting an ‘Oklahoma boomer'” March 28, 1885

SOURCE 5B

“Boomers entering Oklahoma Territory” c1905

SOURCE 5C

“Interview [Mrs. Flora Robertson] about Oklahoma” May 08, 1940

Extra Resources

MORE PRIMARY SOURCES

Oklahoma newspapers in the Chronicling America Historical Newspaper Collection

Dawes Act, 1887 (National Archives, includes secondary source summary)

Curtis Act, 1898 (Oklahoma State University Library)

SECONDARY SOURCES

Oklahoma Historical Society: Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture

Activity Materials

As always, please feel free to download and distribute the activity documents (but please keep the logos). If you like this activity or use it in any way, please let us know. We love learning from you too!

All Activity Sources (4.84 mb)

Common Core English Language Arts Standards Alignment

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grades 9-10

- RH.9-10.1. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

- RH.9-10.2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

- RH.9-10.4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social science.

- RH.9-10.6. Compare the point of view of two or more authors for how they treat the same or similar topics, including which details they include and emphasize in their respective accounts.

- RH.9-10.7. Integrate quantitative or technical analysis (e.g., charts, research data) with qualitative analysis in print or digital text.

- RH.9-10.8. Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claims.

- RH.9-10.9. Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

- RH.9-10.10. By the end of grade 10, read and comprehend history/social studies texts in the grades 9–10 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

- RI.9-10.1. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

- RI.9-10.3. Analyze how the author unfolds an analysis or series of ideas or events, including the order in which the points are made, how they are introduced and developed, and the connections that are drawn between them.

- RI.9-10.4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language of a court opinion differs from that of a newspaper).

- RI.9-10.5. Analyze in detail how an author’s ideas or claims are developed and refined by particular sentences, paragraphs, or larger portions of a text (e.g., a section or chapter).

- RI.9-10.6. Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how an author uses rhetoric to advance that point of view or purpose.

- RI.9-10.7. Analyze various accounts of a subject told in different mediums (e.g., a person’s life story in both print and multimedia), determining which details are emphasized in each account.

- RI.9-10.8. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is valid and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; identify false statements and fallacious reasoning.

- RI.9-10.9. Analyze seminal U.S. documents of historical and literary significance, including how they address related themes and concepts.

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grades 11-12

- RH.11-12.1. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- RH.11-12.2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- RH.11-12.3. Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

- RH.11-12.6. Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

- RH.11-12.7. Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- RH.11-12.8. Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

- RH.11-12.9. Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

- RH.11-12.10. By the end of grade 12, read and comprehend history/social studies texts in the grades 11–CCR text complexity band independently and proficiently.

- RI.11-12.1. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

- RI.11-12.4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze how an author uses and refines the meaning of a key term or terms over the course of a text.

- RI.11-12.5. Analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of the structure an author uses in his or her exposition or argument, including whether the structure makes points clear, convincing, and engaging.

- RI.11-12.6. Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text in which the rhetoric is particularly effective, analyzing how style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness or beauty of the text.

- RI.11-12.7. Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- RI.11-12.9. Analyze seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century foundational U.S. documents of historical and literary significance for their themes, purposes, and rhetorical features.